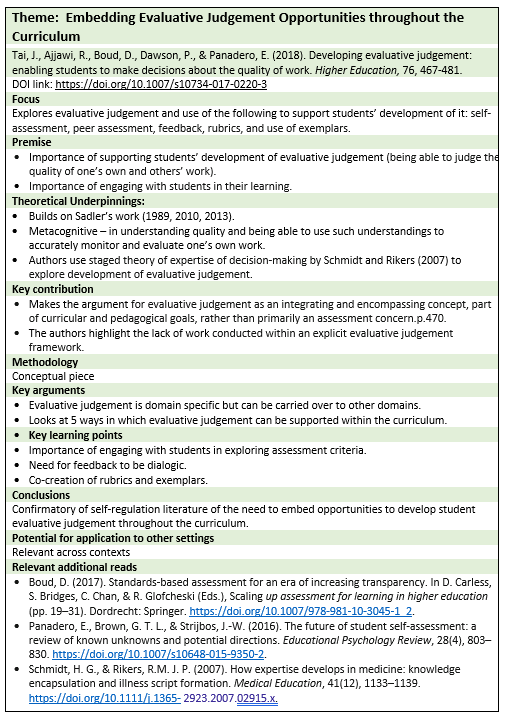

5.9 Self-Assessment Supporting SRL

Individuals who can accurately judge their learning are more effective learners (DiFrancesca et al., 2016).

Self-assessment includes a “wide variety of mechanisms and techniques through which students describe (i.e. assess) and possibly assign merit or worth to (i.e. evaluate) the qualities of their learning processes and products” (Panadero, Brown, & Strijbos, 2016, p.2).

Self-assessment comprises two main components:

self-monitoring (a moment-by-moment awareness of the likelihood that one maintains the skill/knowledge to act in a particular situation)

overall self-assessment which requires a global judgement of one’s ability in a particular domain.

The ability of individuals’ to be able to accurately assess the quality of their own work has been questioned. In disaggregating self-assessment, Eva and Regehr (2011) argue that self-monitoring is generally more reliable in individuals than their overall self-assessment.

The importance of being able to accurately judge the quality of one’s own learning is central to definitions of self-assessment which is seen as a key component of self-regulation. Accuracy in self-assessment (SA) is key to the internalization of standards so that students can regulate learning more effectively (Evans & Waring, 2020; Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, 2013; Panadero, 2017; Schneider & Preckel, 2017).

Notably, self-assessment is moderated by the perfection level that a learner wishes to achieve, which takes us back to goals (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, 2013).

Perfecting self-assessment requires support (Eva & Regehr, 2011). Self-regulation does not happen alone. Accurately calibrating where one is in relation to attainment of goals, and what needs to done, is central to self-assessment. Being able to critically reflect, and to see things in a different way links to Vygotskian notions of the zone of proximal development. Supporting students in learning to use the environment effectively, and to selectively use resource to support enhanced understandings is vital. Scaffolding needs to support students to think in different ways. Emphasis has be on guided mindful activities to avoid the negatives associated with the proliferation of unsupported self-reflection activities that may result in mindless activity given that students will be shackled by existing frames of reference unless there has been sufficient challenge, and exposure to alternative approaches to enable them to question existing strategies (Evans, 2020).

While notoriously difficult to address (Panadaro, Jonsson, & Botella, 2017), there are a number of strategies that have been found to be helpful in developing self-assessment capacity to include:

Integrating SA into all stages of learning process (Boud et al., 2015; Mays & Branch-Mays, 2016).

Promoting the development of self-assessment skills from the outset, prior to completion of a task (e.g., inducting students into the language and meaning of assessment) supports students’ ability to monitor their own learning, and to set and retune/refine goals impacting efficacy beliefs and perceptions of control over their learning which feeds perceptions of self-regulatory capacity.

·Students need to be clear about the criteria being used to assess their work and have active opportunities to engage in the development of criteria.

Providing ongoing opportunities for them to practice their self-assessment skills using modelling, guided activities, approximations of practice to enable students to calibrate what quality is for themselves. While at the same time noting, the importance of individual, co- and shared regulation processes required to support SA, key considerations include. :

Reinforcing the SA experience across the curriculum, using a similar structure of self-assessment throughout a course to increase the predictive value of self-assessment (Mays & Branch-Mays, 2016).

Self-assessment needs to be modelled in an explicit way to support students in self-evaluating as part of the learning process (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, 2013).

Providing explicit tools to support understanding e.g. clearly structured rubrics (Panadero & Romero, 2014; Jones & Alcock 2014) - The Law of “Comparative Judgement” constant comparison of pairs of scripts-‘ human beings are more reliable at making relative judgements of one sense impression against another than they are at making objective judgements of individual sense impressions in isolation’ approach.

Placing students in situations that elicit errors and exposing them first to ill-structured problems followed by well-structured problems can lead to better learning outcomes in line with theories of desirable difficulties (E. L. Bjork & R. Bjork, 2011; Bjork, 2017), and productive failure (Kapur, 2008), as these approaches may encourage students to spend more time, and at a deeper level trying to solve problems. They also draw on retrieval of information and metamemory, memory of what you know.

Need for challenge - overreliance on well-structured problems causes students to be underexposed of recognising, representing, and justifying problems (Kelly et al., 2016).

The power of feedback to support self-assessment understanding is important. Situations need to be created for learners and teachers to experience the limits of their competence in the presence of feedback. Improvement strategies need to be tailored to those experiences rather than on self-assessment alone (Eva & Regeher, 2011). As part of this students need comprehensive opportunities to mark and give feedback on work of others (Nicol et al., 2014).

Key Concepts: self-monitoring, self-evaluation, accuracy, internalisation of standards

ACTIVITIES

1. Map student self-assessment opportunities throughout a programme.

2. Engage students in ‘approximations of practice’ – opportunities to replicate the marking and moderation panels and processes that are used within your institution.